Managing Water in California Agriculture – understanding legal and logistical challenges is the first step for farms looking to manage water. Four experts provide advice.

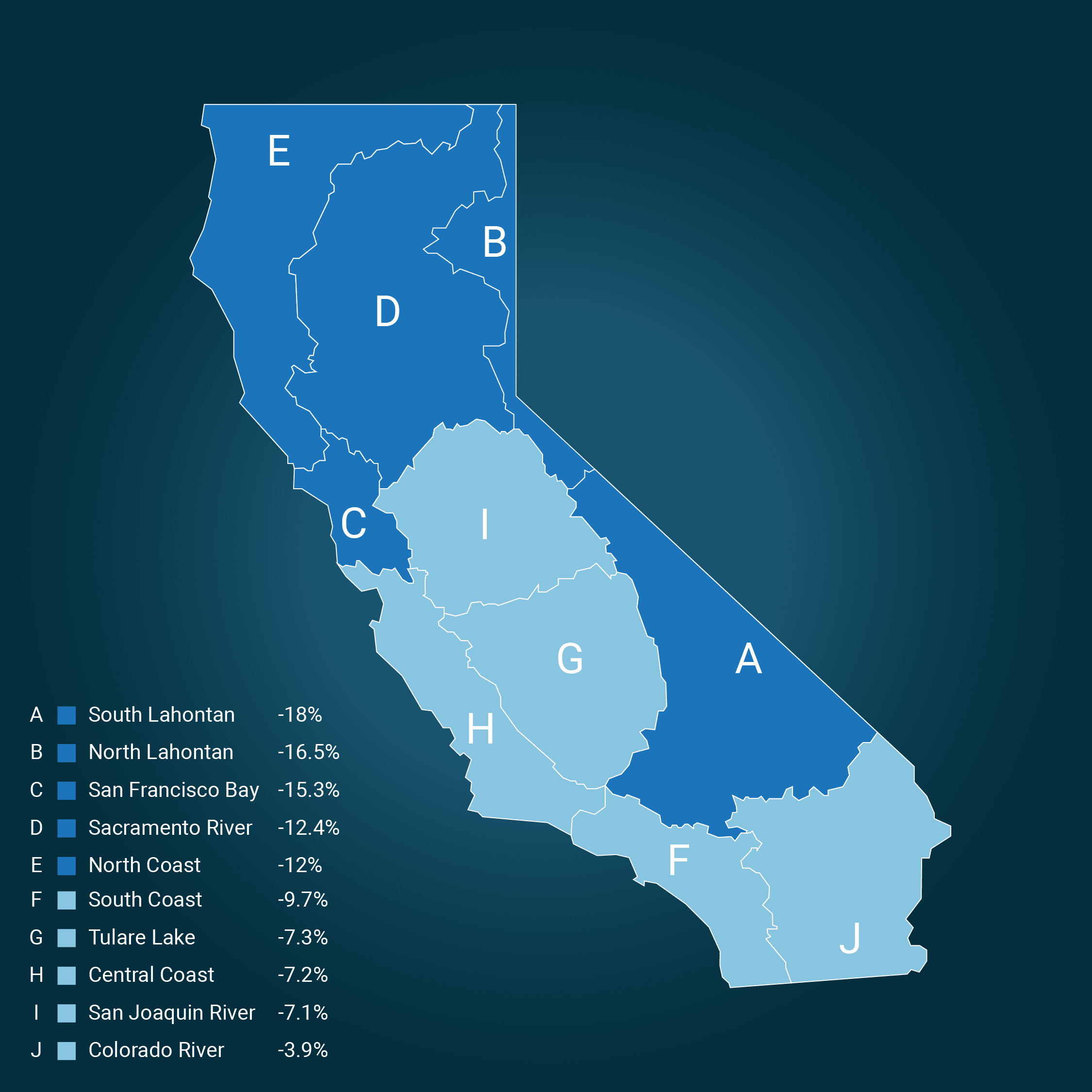

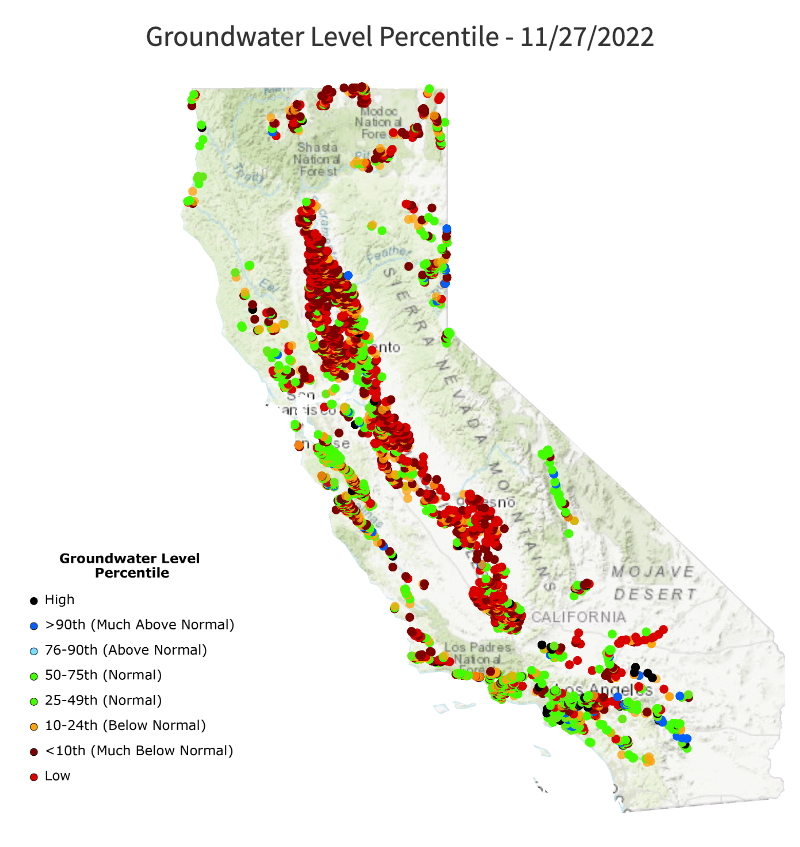

Each year California’s agriculture industry uses approximately 34 million acre feet of water to irrigate 9.6 million acres, while bringing over $20 billion into California’s economy.¹ The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act uses a patchwork of local agencies to manage access to this water. In 2021 the California Department of Water Resources announced that, as a result of dry conditions, it only expected to deliver 5% of requested supplies.² The challenge is an existential threat to many farms, some of which are generations old.

We all understand that access to water is the top concern for Californian agriculture. If you work in the industry, what can you do to best plan for your future? The imperative to ensure that there is sufficient water to grow a crop is as old as agriculture itself, but increasingly tight regulations and water supplies pose new challenges that must be addressed.

“We’re in a much tighter regulatory world than we were in ten years ago,” says water rights lawyer Rebecca Smith, who is a partner at California’s Downey Brand. As a water expert, Smith understands the urgency of the situation and spends much of her time educating and advising clients on the logistics and legalities of water management.

“I have a client that has an 80-year-old family farm, and they’re going out of business because they can’t afford to keep the water on,” she says.

Forward thinking ag producers like Jack McCarthy understand the importance of proactive action.

“We spend a lot of time on water, understanding the rights that we have today, the quality and security of them, and how they will change over time,” says the Co-founder and CEO of Gold Leaf Farming.

As laws morph, tighten, and evolve, staying up to date is no small feat.

California Water Law and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act

Not only are laws regarding access to water becoming tighter, they’re becoming more difficult to parse and keep track.

“California, in particular, can turn keeping track of the rules surrounding your water supply into a full time job,” says Smith.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA, passed by the state in 2014, gives enforcement authority and responsibility to local agencies on a basin by basin basis. The patchwork approach to regulation requires those in the industry to stay on their toes.

“If you’re growing peaches in Yuba, the regulatory world you’re looking at, especially for groundwater, is 180 degrees different than it would be for even the same crop in another county 200 miles south,” Smith explains.

Marisa Alcorta is Program Manager at the Center for Land Based Learning, headquartered in Woodland California. Alcorta, who also operates a small farm with her husband in Northern California, believes that swift state action is necessary to better manage the situation.

“The state has allocated lots of money for water storage, but they haven’t done anything with it,” she says.

“The projects are glacial at this point. I feel like the government needs to wake up and move with urgency, because it’s not a small problem anymore.”

Professional Help Important for Water Management

“If you’re a business, operating in California in particular, you need to have somebody who’s dedicated to managing your water,” advises Smith. “People come to me and ask: ‘what’s going to give me heartburn?’” Companies will often task an in-house employee with keeping track of the day to day developments, calling in outside legal help as needed.

Smith advises producers to choose their help carefully.

“Lawyer or not, you need people who are plugged into what the local conditions are,” she says. “You have to spend time understanding both the physics and the rules of the place. When the drought hits, everybody with a bar card says they’re a water lawyer,” she says. “There are large companies who have lawyers in New York, and when they have to do a due diligence project, they call me specifically for that.”

McCarthy explains that Gold Leaf rely on outside help to manage the situation.

“We use water attorneys, hydrologists, and other water experts to help us understand it,” he explains.

Given the large financial consequences of land acquisition, it makes sense to err on the side of caution.

“We do a lot of due diligence as we look for new farms to acquire,” says McCarthy. “Our goal is to buy farms that we can hold forever and that means they need to have really good water. We need to be careful about where we try to farm almonds, pistachios, and other future crops. It’s something we talk a lot about.”

Not only is it important for companies to weigh the particulars of local law and water resources, but also their unique strategies and situations.

“So much of what you do with water is dependent on the way that you’re using your property,” says Smith. “You need someone who understands what has value to you.”

Utilizing Technology to Improve Water Efficiency

Since farms are being challenged with decreasing water supplies, the obvious task at hand is to do more with less. While this is certainly a significant challenge, technology is helping growers make advancements.

“The growers of California have done a lot to improve irrigation efficiencies and grow their crops in a manner that’s better for the environment,” says Aric Olson of Jain Irrigation, who specialize in drip irrigation and precision irrigation technology.

McCarthy discusses Gold Leaf’s utilization of the Hortau irrigation modeling system, which has both elementary and in-depth functionality.

“Some of it just sort of tells you if the water is on or not,” says McCarthy, “but it also gives you a sense of how hard the roots are pulling on water. We trialed it at one farm for a year and it worked really well, so we use it almost everywhere now. It gives us a really good ability to optimize water, which is obviously super important.”

While drip and micro irrigation are more efficient than flood or sprinkler irrigations, they’re also more expensive and, thus, lag behind in terms of global uptake.

Olson touts the technology’s advantages, “It allows you to put exactly the right amount of water and fertilizer, right at the root of the crop. You’re really doing what’s good for the crop and the environment.”

The potential for increased precision is the result of a convergence of developing technologies, a trend that Olson expects to continue.

“This will be the decade of vision tools in agriculture,” he says confidently. “We have high resolution satellites that can focus down to the tree level. We have good fixed wing aircraft solutions that can do flyovers and get very good granular photos of the fields. Drone applications are going to be popular that can produce yield estimates, disease predictions, and all kinds of modeling.”

Coupled with local weather data and soil moisture probes, this satellite technology will enable the optimization of water and fertilizer schedules, potentially saving a substantial amount of water.

Easements and Crop Changes May Make Sense

If irrigation techniques are not sufficient to address water shortfalls, a reassessment of land use with an eye toward more efficient crops may be in order.

“Almond trees need water every year of the tree’s life, no matter what” says Olson. “The trees don’t care about a drought situation.”

Other crop configurations offer greater flexibility.

“If you have a couple of thousand acres of tomatoes, or cotton, or alfalfa, you could have that land go fallow, or use it for a crop with less water requirements.”

Smith explains that producers looking to reassess their land usage can find financial support in the form of easements from non-profit and federal agencies. As she describes it, some of these easements are fairly in tune with the industry’s needs.

“Many conservation easements are compatible with your existing agriculture production. If, for example, you are maintaining habitat for an endangered hawk, you may not be able to have activities in certain areas where the hawks may be nesting, and perhaps may have to provide nesting boxes, but you’re still going to be able to continue with your cultivation activities,” she explains.

Water Transfer is a Complicated Process

In addition to diversifying their crops, those in the industry often attempt to diversify their water sources. While such an approach is proactive and prudent, Smith warns that it’s not a magic solution.

“Some folks have 80% of their water needs covered and buy land with water rights elsewhere in order to transfer it,” she explains. “Being able to transfer that water, especially out of basin, is dependent not only on infrastructure, but also on regulatory regimes. It might be unduly optimistic.”

In addition to managing the water that comes onto their land, farmers must also be diligent about any water leaving their land.

“If you’ve got water that is coming off your property, you need to know and understand where it’s going in order to avoid putting yourself in a world of hurt,” says Smith. “If water comes off of your land and contaminates a river, or discharges into a regulated water body, you have the potential for very big fines and years of litigation. Planning ahead and understanding the details matters.”

Smith believes that the key to successful water management is education and proactivity, so she urges action, particularly for those looking to take advantage of easements or change their land uses.

“If you’re in a strong position and you have enough water for next year, maybe now is the time. Don’t wait until you run out of water to figure out what you’re going to do with the land. Agriculture has a target on its back. We’re not going to turn off the water at the hospital.”

For his part, Olson sees potential for those willing to embrace innovation.

“The technology is working,” he says. “Autonomous irrigation is coming. We’re in a pretty unique time.”